Mom and I went to the dinner celebrating all of the transplants. It was a really nice event. I met a boy who reminded me a lot of you. I just wanted to hug and squeeze him but he didn't know me. He might have thought I was weird. So I settled for a handshake.

His name is Tucker. He is a racing fan so I am going to get him an XM radio so he can listen to the races.

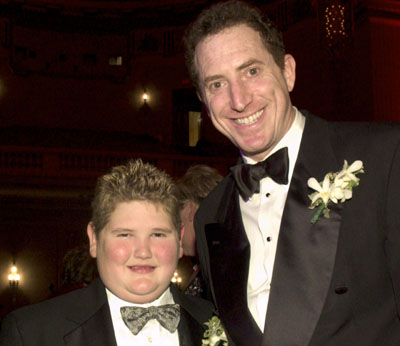

The dinner was a very special occasion for our friend and the man I work for -- Hugh -- and his wife Mary Beth. Hugh won an award and said something incredibly sweet about you in his acceptance speech. I cried. He is a great person. You would have liked each other a lot.

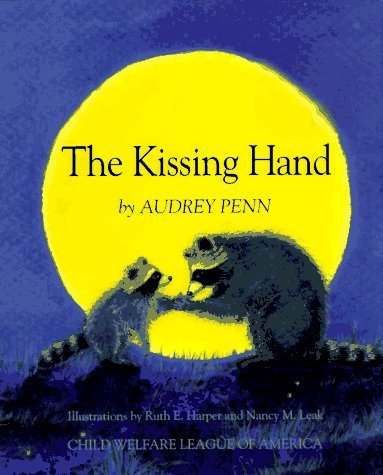

Then Mary Beth met her donor for the first time. It was a wonderful moment. I thought back to when you and I met with Beverly for the first time. She brought you that book, The Kissing Hand. She is a terrific person.

I wrote something for someone who was speaking at the dinner and when I wrote it I was thinking of Beverly and of Mary Beth's donor.

"But what brings us all here tonight could not be more inspiring. Individuals giving of themselves – literally – to save the lives of others whom they do not even know. Each of the 20,000 transplants that we celebrate tonight is a miracle of science and testament to the power of love. ...

There is a single thread that joins us all. For some that thread may get frayed or broken, but fortunately there are those who will share the strands, the very fibers that run through them, to make the ties that bind us all together even stronger."

The dinner was in a place that has a lot of meaning for me and Mommy. Years ago I worked for a man named George Koch. He was retiring from the place where he had worked forever. My friend Kathy and I worked for him and we hired Mommy to organize a dinner in his honor. The dinner was held in the same room as the one we went to last night. Mr. Koch's dinner was a fundraiser for the Crohns and Colitis Foundation of America. Mr. Koch's daughter Lucy has Crohns disease.

That is me and Mr. Koch. Kathy is to the left of Mr. Koch. Doesn't Mommy look young. We didn't know each other all that well.

Yesterday afternoon I was walking over to check on the arrangements for the transplant dinner, and I was reading email on my phone (isn't that crazy!). I saw that Kathy had sent me an article about Mr. Koch. That was a cool coincidence.

The article is great. I hope that Jack and Joe can work for men like Hugh and George Koch. They have been great influences in my life. I've been really lucky that way. Someone at the transplant dinner described himself as the luckiest unlucky person ever. I feel that way, too.

The only problem with the article about Mr. Koch is that it didn't talk about how great he was taking care of Lucy. The way that he made sure she got the best medical care and saw the best doctors was an inspiration to me - though I didn't know it at the time. I learned many important things from him but maybe this was the most important of all.

You met Lucy one day when we were at Chicken Out over on Massachusetts Avenue. She is doing great and has her own family now.

November 15, 2004 Monday

Koch's K Street Orbit

By Brody Mullins ROLL CALL STAFF

If K Street has a godfather, his name would be George Koch.

In nearly a half-century as one of Washington's top corporate lobbyists, Koch, now 78, boasts of one of the broadest networks of proteges on K Street, thanks to years of hiring budding lobbyists.

Koch usually took in promising people not long out of college, gave them major responsibilities and worked them to the bone.

Among the dozens of young lobbyists who worked for Koch (pronounced "Cook") when he was head of the Grocery Manufacturers Association are James May, president and CEO of the Air Transport Association; Tom Wheeler, the former chief of the Cellular Telecommunications & Internet Association; Larry Harlow, the president of Timmons & Co.; and Ed Merlis, the chief lobbyist for the U.S. Telecom Association.

"He really taught me the game," said Jace Hassett, the vice president of government affairs for Occidental Petroleum, who worked for Koch as an intern and later as an employee in the late 1980s. "It was almost like taking a graduate course in political advocacy and government affairs."

From 1966 to 1990, when Koch was president of the Grocery Manufacturers Association, Koch trained about two dozen lobbyists who remain in the K Street fray today.

Other alums of Koch's office include Stephen Gold of the National Association of Manufacturers; John Gray of the Healthcare Distribution and Management Association; Jane Hoover of Proctor & Gamble; Kathy Ramsey of the National Association of Broadcasters; and Tuckie Westfall of Altria Corp.

In addition to his surrogate family of lobbyists, two of Koch's own children have carved out successful roles on K Street.

One son, Robert Koch, was recently promoted to CEO of the Wine Institute after a long career as the institute's senior vice president.

Another son, P.C. Koch, is a successful telecommunications lobbyist whose clients include AT&T.

The elder Koch ran the Washington office for Sears, Roebuck and Co. for six years, beginning in 1960 before taking over the Grocery Manufacturers Association. There, he began relying on a young but promising group of lobbyists to represent the largest U.S. grocery manufacturers, including Kellogg, General Foods and General Mills.

"I had a philosophy when I was at GMA," said Koch, now a lobbyist with Kirkland and Lockhart. "Hire 'em young, train 'em well, and move 'em on."

Gary Kushner, a lobbyist who began with Koch in 1976, recalled his former boss's doctrine.

"He would tell us: 'The day you start here is the day you start looking for another job, because there is only one job worth having here - and I am not leaving,'" said Kushner, now a food lobbyist with Hogan & Hartson LLP.

Added former aide Harlow: "He would work them into powder and expect them to get the heck out. Anyone worth two bits would turn around and find a better job somewhere else."

Kushner, Harlow and others said Koch forced his staff to learn the business by giving them plenty of responsibility, working them hard and coming down on them for even the smallest of mistakes.

So fastidious was Koch that in the days before electronic typewriters he would hold type-written letters up to a mirror to see if his staff had used white-out to cover up typos. If they had, he would make them retype the letter.

If you can't do the little things right, he figured, how can you be expected to do the big things right?

Koch - whose staff addressed him as "Mr. Koch" - expected underlings to work long hours for him.

"He would say, 'I own you from the first thing Monday morning to the last thing Friday night, and the weekends are for your family,'" said Kushner, who kept an extra pair of underwear and socks in his drawer.

Workdays for Koch and his lieutenants often began with a 7 a.m. breakfast at the University Club. There, Koch would eat a cheeseburger - "the most nutritious meal for breakfast," he would say - and map out the rest of the day.

Koch's frugality extended from these breakfast meetings to the salaries he paid his staff.

"We lived on air and water," said one former employee, who requested anonymity.

"You can either hire talented people and pay them a lot and try to keep them, or do what he does, which is giving very young people a chance to prove themselves," added Koch alum Hassett.

One of the central lessons Koch taught budding lobbyists was the value of being truthful to Members of Congress and the administration.

"He had an extraordinary work ethic and he taught us everything from a good, core ethical sense of how to do business," said May, who took his first job with Koch at age 14 in the early 1960s. "He drove into us all that all you have as currency is your good name."

Perhaps no one underscores Koch's sense of morality better than one of his greatest adversaries, Michael Pertschuk.

In the 1970s, Pertschuk, a liberal Democrat on the Federal Trade Commission, battled with Koch and his well-heeled group of food manufacturers over a proposal to create a powerful new federal regulatory body called the Consumer Protection Agency.

Yet in his 1986 book "Giant Killers," Pertschuk lionized Koch as "a remarkable - and good - man," recalling how his one-time adversary took him to lunch at the Four Seasons to cheer him up as the Reagan revolution swept into Washington.

"He'd figured that the day after the Reagan inaugural, facing my imminent fall from grace and power, feeling displaced and forgotten, I'd need a dose of cheer - a dash of reassurance and a good meal," Pertschuk wrote.

About the same time Koch was battling Pertschuk over consumer protection at the FTC, he was involved in a more personal fight that sheds light on his principles.

When a black employee of the Congressional Country Club tipped off Koch, a club member, to a wage-skimming scam at the club, Koch launched a protracted legal fight to recover about $1 million in wages allegedly taken from its prominently black and Hispanic staff.

Beginning in the late 1970s, Koch spent more than five years and $100,000 of his own money on a bitter legal battle with the club's board of directors.

"If you didn't know that George Koch was a white, middle-class conservative Republican lobbyist for the grocery manufacturing industry, you might think he was Martin Luther King, Jr.," wrote a prominent black newspaper, the Washington Afro-American. "Certainly their stories are similar and Koch's courage appears to be as great."

In the early 1980s, Koch and the board of Congressional Country Club reached an undisclosed settlement to reimburse its staff for wages going back for decades.

The episode left an impression on Koch's employees.

"George Koch was Mr. Straight Arrow when it came to ethics," said Wheeler, who worked for Koch during the Watergate era. "To this day I consider myself incredibly blessed because it was George who showed me how it works. I understand the juxtaposition with other folks my age at the time."

In a recent interview, Koch placed ethics and character at the top of his list of lessons his employees had to learn.

"It makes me feel very proud because they are morally straight and they do a great job," Koch said. "They made me what I was at the time. They made me successful, so the chance to see them succeed is a great way to leave - not that I am going anywhere."

No comments:

Post a Comment