We had a nice weekend. Baseball on Saturday - Jack hit a homerun - and another march on the mall on Sunday. We walked with other families to support a kid a JPDS who has juvenile diabetes.

I was glad to see how many families turned out for the march. But at the same time I was sad to know that there would never be a "march" for Fanconi anemia. I said to Jack that it is crazy, but one of the problems with Fanconi anemia is that not enough people have it. You don't want anyone at all ever to have it, but you want there to be enough people to care, enough people to march, enough people to contribute money and enough people to try to find a cure.

I read the Fanconi anemia newsletter last week and Dr. Wagner wrote that they are having more success with unrelated transplants in Minnesota. Again, it is great for everyone going to transplant now and in the future... but hard for me to read.

I also saw this today. Wouldn't it be great if they can cure FA. There are only about 1,000 people in the entire world with it. No-one should ever have to go live with what you and they have lived with. No families should ever have to go through what we've gone through.

New Studies Give New Hope for Rare Disease

Study, Funded by the National Institutes of Health, Will Research Over 20 Conditions

May 7, 2006— - In the next few months, the National Institutes of Health will launch over 20 new studies into rare diseases at about 50 sites around the United States and in other countries.

A rare disease is defined as a disease or condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people in the United States. By studying such rare diseases as genetic steroid defects and pediatric liver disease, researchers hope to develop more treatments and drugs for patients who might otherwise be overlooked by the medical and pharmaceutical community.

At first glance, you would never know that 2 1/2 year old Erick Benitez nearly lost his life when he was just three days old. Erick suddenly fell into a coma and suffered mild brain damage.

Doctors soon discovered that Erick had a rare urea disorder, a genetic condition where the body lacks the enzymes necessary to break down protein into urea and excrete it in urine. The disorder is so rare that it affects only one in 100,000 infants.

"There is no newborn screen for urea cycle disorders in the same way there is for a number of other rare disorders" said Dr. Mark Batshaw of Children's National Medical Center. "So, we have to wait until the child becomes ill before we can actually make a diagnosis."

New Hope

Twenty-five million Americans suffer from rare diseases, about 6,000 of which have been identified like Rett Syndrome, a childhood neurodevelopmental disorder which almost exclusively affects females; Giant Cell Arteritis, an inflammation of the lining of the arteries; and cystic fibrosis, a genetic disease that causes life-threatening lung infections.

"The aggregate number sounds in fact quite large, but when you break it down into many different diseases, thousands of them, there are only a few hundred in each category, so there hasn't been any incentive for the drug company to study these," said ABC News Medical Editor, Dr. Tim Johnson. "There's no real profit and the only way for it to happen is for the federal government to put in research."

But now researchers say by testing new drugs in these federally-funded clinical trials, new treatments may be possible -- giving hope to many families.

"One of the unique things about rare disorders is you never know where the research is going to go," said Dr. Stephen Groft the directory of National Institutes of Health's Office of Rare Diseases. "So, it is not too unusual for the findings in rare diseases to be applied to the more common disorders and vice versa."

Batshaw is optimistic the new clinical studies will help Erick -- a young boy with a bright future.

"It's possible that we will develop a better medication so that you'll have to use less of it," he said to Erick's mother.

Within the next five to ten years Batshaw hopes to develop a test to screen all newborns for urea cycle disorders so no child suffers brain damage or dies from the condition -- a goal now closer than ever with the new clinical studies.

For more information on rare diseases visit the NIH Web site the National Center for Research Resources Web site and the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network Web site.

ABC News Medical Editor, Dr. Tim Johnson, originally reported this story.

Copyright © 2006 ABC News Internet Ventures

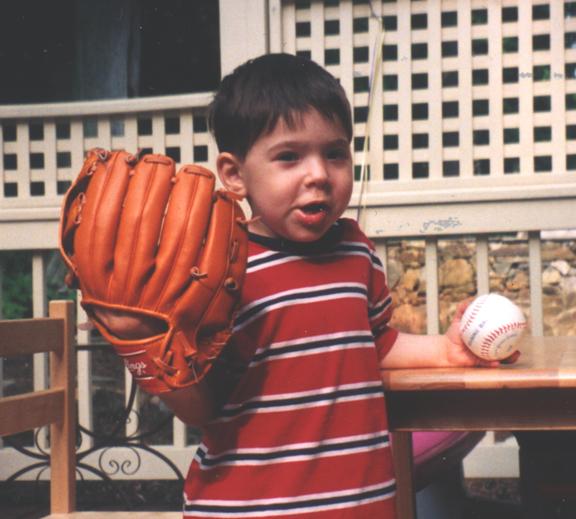

This was you early in your baseball career. You were very cute. If only that career was starting now, not in 1995.

No comments:

Post a Comment